The third of the SOLID principles is the Liskov Substitution Principle and it can be paraphrased as follows:

Objects in a program should be replaceable with instances of their subtypes without altering the correctness of that program

Barbara Liskov

Basically this tells us that every subclass should be interchangeable for their base/parent class.

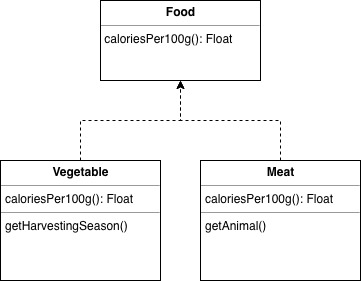

To better understand it, let’s imagine to have a base class called Food with two sub-classes Vegetable and Meat.

We see that both sub-classes inherit the function caloriesPer100g() and also add one specialized function each, depending on their nature. We can therefore assign an object of type Vegetable or that of type Meat to a reference of type Food and invoke on it all functionalities acquired via inheritance.

The Liskov substitution principle assures that what will be invoked is in fact the actual object’s overridden implementation of these methods.

Food food = new Vegetable();

Float calories = food.caloriesPer100g();

food = new Meat();

calories = food.caloriesPer100g();

Violation of the principle

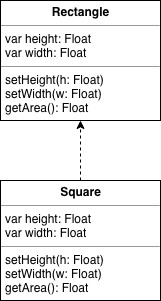

When applying the Liskov principle one could tend to apply a IS A relation between the classes, assuming for example that a Vegetable IS A Food. This is not per se a wrong assumption, but we need to be careful because it could lead to misleading scenarios like the following. Let’s imagine to have a base class called Rectangle with a sub-class Square.

Inherently a Rectangle can have its height and its width different and freely changeable (ok ok they should still remain non null positive numbers), but this doesn’t hold up for a Square which inherently needs to have equally long sides.

In this case the setHeight() and setWidth() of the Square behave differently and need to set both parameters, creating a violation of the Liskov substitution principle.

In the following posts I will discuss the next principle highlighted by the SOLID acronym, the Interface segregation principle

Leave a Comment